Marketplace Monetization Comes At A Price

A framework for classifying platform / marketplace businesses through a pricing lens.

“In construction, a platform is something that lifts you up and on which others can stand. The same is true in business. By building a digital platform, other businesses can easily connect their business with yours, build products and services on top of it, and co-create value.” - Harvard Business Review, Three Elements of a Successful Platform

Marketplaces are one of the defining business models of the internet age. Amazon matches sellers with buyers, Uber connects drivers and riders, Airbnb brings together hosts and guests, and so on. Their strength lies in network effects - more users attract more suppliers, and more suppliers attract ever more users, and so on. But network effects alone do not guarantee success. Pricing is just as critical. Venture Capitalist Bill Gurley argued in his work on marketplace dynamics that the rake a platform takes shapes who joins, who stays, and whether the business endures. Ben Thompson, writing on Stratechery, explains in Aggregation Theory that platforms win by controlling demand, serving additional users at near-zero marginal cost, and commoditizing suppliers.

Building on those ideas, I classify marketplaces and platforms1 by their pricing power - what they can charge, and what they must give up - into four kinds:

Paid Cross-side Platforms – These platforms create value primarily by enabling direct exchanges between its consumers and producers, and benefit from cross-side network effects, i.e. the volume and nature of merchants attracts users, and more users attract more merchants. Interaction is cross-directional, from sellers to customers and customers to sellers. Customers do not typically interact with other customers (and merchants do not necessarily interact with other merchants). Examples are eBay, Amazon Marketplace, Alibaba’s Tmall, Uber, Lyft etc. I call them paid platforms because they charge merchants a rake (also known as revenue share or commission or transaction fees) when they sell to customers. Paid platforms are typically rake-elastic: if fees rise too high, sellers will look for cheaper alternatives. With no hardware or infrastructure lock-in, competitors can lure sellers away by offering lower fees. Managed platforms are an exception. They can sustain higher rakes if customers or merchants see value in the oversight and service they provide.

Hardware Cross-side Platforms – Cross-side platforms or marketplaces built on top of a hardware or infrastructure layer are unique because these platforms do not typically attract users by the volume and nature of the merchants on their platforms; rather the hardware attracts users, and the users then attract merchants. In some cases, unique infrastructure (warehouses, delivery mechanisms, curated storefronts) pulls in merchants on its own. In either case, because demand is captive to a locked-in installed base and/or the platform offers infrastructure that sellers can’t get elsewhere, these platforms are more rake-inelastic, and can charge higher rakes without losing their best suppliers. Examples include Apple Appstore, Xbox Gamestore, Google Playstore. Theoretically, even a physical marketplace in a unique location that allows merchants to sell their wares, and charges them on a revenue share model falls in this category. Fulfillment by Amazon fits here too: its vast warehouses and logistics network are costly to copy, giving Amazon structural bargaining power to set storage/fulfillment fees.

Free Cross-side Platforms – These platforms charge neither consumers nor producers at the point of exchange. Exchanges between their consumers and producers are almost always free. Instead, they turn attention into currency: more users bring more engagement, which advertisers then pay to access. They benefit from cross-side network effects. Google and Yelp are examples of this kind of platform. Pricing power comes not from rake, but from audience quality, auction dynamics, and measurable ROI. Platforms with affluent, high-intent users sell scarcer attention, and if ads convert and targeting is superior, bids rise.

Same-side Platforms – These platforms create value by enabling direct exchange amongst its users, and are monetized either by charging the users directly (rare), or by charging advertisers to sell services to users (most often). Messaging apps, social networks, and communities are examples, and these platforms benefit from same-side effects (more users -> more users) and once there is a valuable installed base, one-way cross-side effects (more users -> more advertisers). But note that more advertisers do not directly mean more customers. In fact, more ads -> bad customer experience -> fewer customers. WhatsApp, Facebook, WeChat, Skype are examples.

Some companies sit across multiple models but products typically pertain to one model. For example, Google is a Free Cross-side Platform for search, but Gmail is a Same-side Platform.

Based on the above classification, the question is: given a platform business model, how much rake can the marketplace bear?

Paid Cross-side Platforms are more rake-elastic because a competing platform with lower rake can attract both sellers with lower fees and customers (when sellers then pass the lower fees to users as lower consumer prices). Hardware Platforms get away with higher rake because of their hardware differentiation. For example, Apple’s Appstore can get away (and they have for 15+ years) with charging developers a high rake (the famous 30% Apple Tax) because even if a competing platform like Android offered a lower rake (say 5%), users are unlikely to switch as long as Apple’s hardware remains attractive. Change is more likely to come from regulators than from competitors. In Free Platforms, prices charged to advertisers don’t (directly) affect the prices on customers, so theoretically new platforms cannot undercut the price (charged to advertisers) of the dominant platform and capture more users. Similar to Free Platforms, prices charged to advertisers in Same-side Platforms don’t (directly) affect the prices on customers, so theoretically new platforms cannot undercut the price of the dominant platform and capture more users. The way to capture marketshare is to offer differentiated service (Facebook vs. Myspace, Snapchat vs. Facebook).

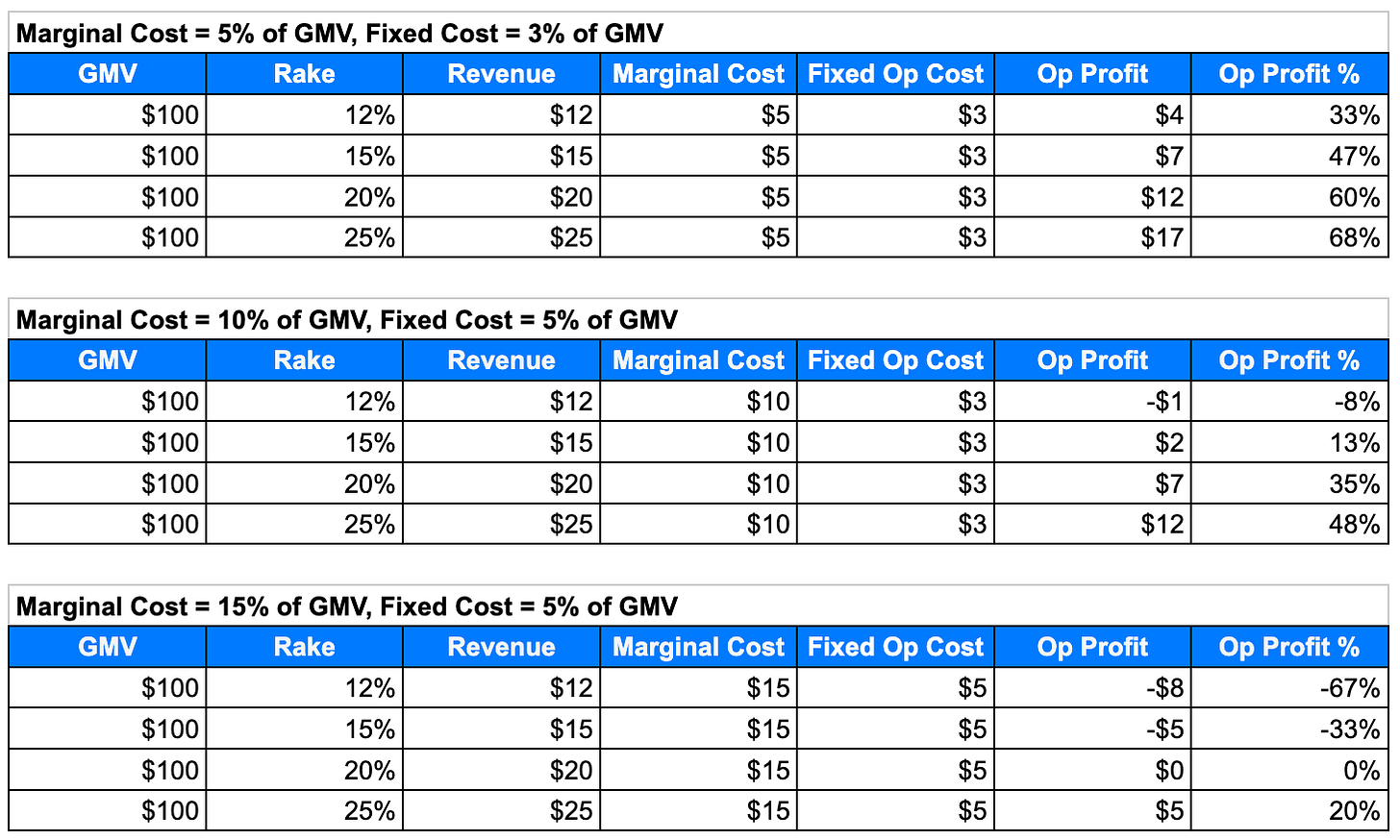

From a cost point of view, there are three costs at play in any platform business. An upfront capital expense incurred in developing the platform (primarily in software development, in some cases physical assets and hardware costs), fixed operating costs that do not vary with each unit of output (i.e. expenses that are largely constant over a range and only step changes as the platform grows such as office rent, most employee salaries), and variable costs that vary with each unit of output (i.e. costs that vary with the number of sellers and customers serviced such as platform maintenance costs, customer service, payment processing).

A balanced marketplace pricing strategy recognizes all three critical factors: the platform’s position on the pricing-power spectrum above, the underlying cost structure, and the availability of patient capital.

In early stages, especially if capital is scarce, a platform may need to charge a rake high enough to account for capital expenses, and fixed and variable costs as a percentage of Gross Merchandise Value (GMV). This ensures sufficient cash flow to keep the business viable. But it will also mean slower seller (and thus customer) acquisition for the platform.

Eventually, as upfront investments are depreciated and fixed costs are spread over more customers and orders, capital expense falls as a share of GMV. So, at scale, the optimal rake should sit only a touch above marginal variable costs with a buffer to cover fixed costs. Such a low but sustainable rake attracts sellers and keeps prices low for customers. But more importantly it is prohibitively hard for new entrants to match/undercut.

As seen in the table above, depending on the type of platform and the cost structure, high rakes on low marginal cost invites lower-rake entrants. Pricing just a bit above marginal cost + fixed cost buffer is the sweet spot where the platform balances seller acquisition, low prices for end-consumers, and long-term defensibility. So the next time you are deciding on the pricing strategy for your platform, note that some rakes are more hazardous than others2.

In traditional tech-speak, platforms are those where other software developers can build applications and software on top of the platform application/software. I take a broader view of platforms, one that includes marketplaces for sellers and buyers to connect, or advertisers and customers to interact.

This article is an edited version of blogpost that was first published on my now-defunct blog in 2017.